By Suzanne Kamata

I first learned of Okunoshima from a Canadian friend’s Facebook post. She’d shared photos of herself surrounded by rabbits. The island just off the coast of Shikoku and only accessible by ferry, was overrun with these adorable animals. How unusual, I thought. How cute! Surprisingly, few Japanese people that I talked to seem to know about this place. However, when it was featured a few months ago on a TV travel show, my daughter Lilia told me that she wanted to visit.

“It’s really far,” I told her. “At least three hours by car.”

“We can take the bus,” she signed to me. (My daughter is deaf.)

I knew that there were no buses that went from our town in Tokushima, on the eastern part of Shikoku, to Tadanoumi in Ehime Prefecture where we could board the ferry to Okunoshima. My daughter, who has cerebral palsy, uses a wheelchair, and it seemed like too much of a hassle to take the bus to Matsuyama and change buses once or twice to get to that tiny coastal town, but I wanted to visit as much as she did. I was charmed by the idea of an island full of bunnies. When I came across a flyer advertising a one-day bus tour to Okunoshima, I immediately signed us up.

We got up extra early that sunny Sunday and met our tour guide in a gravel parking lot near the town gym. I’d told the tour guide that my daughter was disabled, but it wasn’t a big deal. We climbed into the front seat and the guide handed out tea and packaged rice balls. We gazed out at the lush green terraced fields, yellow roadside wildflowers, and flooded rice paddies as we made our way to Ehime Prefecture. The landscape outside our window might have been lifted from the animated film Tottoro.

“Inaka,” Lilia signed.

“Yes.” I agreed that we were deep “in the countryside.”

I was a little worried that once we got to the island my daughter would find the real-life rabbits annoying. I remembered how she had been bothered by the notoriously aggressive deer in Nara on her school trip. One deer had tried to eat her notebook. What if the rabbits tried to nibble on her fingers or cellphone? But as we rolled along the highway, she reminisced about the rabbit she and her classmates had taken care of in kindergarten, When it had died, they had held a little ceremony and buried it on the school grounds.

As we approached the port, finally catching a glimpse of the sea, the tour guide gave us some final instructions. “Don’t give the rabbits snacks,” she said. We could buy rabbit food at the port.

The bus took a turn down a narrow road flanked by brown-tiled houses, many of them with solar panels. Finally, we arrived at a parking lot next to a small cluster of buildings. To my surprise, here we were, seemingly in the back of beyond, but a long line of people already snaked around the corner from the ferry dock. The tour guide seemed a bit nervous. “It’s a small boat,” she said, “and they don’t accept reservations.” She hurried off to buy our tickets. Note to self regarding future visits: arrive plenty early.

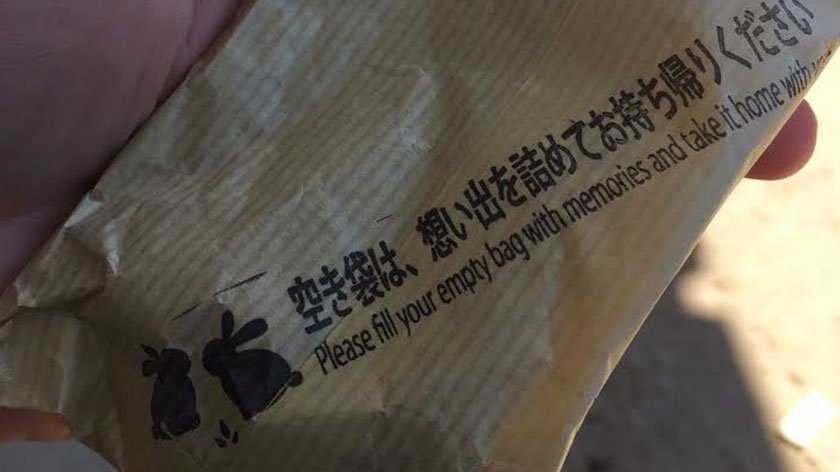

The tour guide returned to the bus and informed us that the passengers were lined up for an earlier ferry and that we would be able to board. Phew! Since we had about half an hour before our own departure, we all got off the bus. Lilia and I went to a small building with a big clock to buy packets of rabbit pellets.

When it was time to get on the ferry, we were directed to the lower level, along with several young families with strollers. Most of the other passengers went above deck. We stayed to the side as three rows of cars were directed onto the ferry. It was shaded and cool.

Lilia, who has always been far more social than me, tried to get me to start a conversation with a blonde foreign woman standing nearby with her three kids and husband. From the familiar scent of her sunscreen, I assumed that she was American, but I didn’t really feel like talking. I resisted my daughter’s entreaties, suggesting that we just relax and enjoy the wind on our faces, the sight of the waves. I thought it was remarkable, however, that although most Japanese people I’d mentioned the island to had never heard anything about Okunoshima, there seemed to be several groups of foreigners on this ferry alone bound for the island.

We arrived in about twenty minutes. The tour guide had arranged for a mini bus to transport my daughter and me to a restaurant on the island. Lunch was included in our package tour. The rest of the group would be going on foot. The restaurant was only about a fifteen-minute walk from the port.

I had half-expected hordes of rabbits to greet us upon disembarking, but it was hot. The first rabbits I spotted were lolling beneath bushes, their energy apparently sapped by the high temperatures and humidity.

My daughter and I boarded the waiting van. I pointed out rabbits to Lilia: there, in a burrow, there, under the picnic table. It occurred to me that this was the first Japanese island that I had been on that wasn’t home to stray cats.

“Are there any predators on this island?” I asked our driver.

He thought for a moment. “Maybe crows.”

The rest of our group was dining in a tatami room. Because of my daughter’s wheelchair, we ate in another room at a table with chairs. Our pre-ordered lunch consisted of slices of sashimi, miso soup, and rice mixed with vegetables, but at the Usagi Lunch Café, you could order pancakes branded with bunnies, white rice molded into rabbit shapes surrounded by curry, and long-eared rice-filled omelettes.

After lunch, we were free to do as we liked until the ferry departed. We set out to explore. Bicycles can be rented, but it’s possible to walk the four kilometers around the entire island in an hour or less. The bunnies are not hard to find.

Lilia and I ventured on to a grassy lawn, which was full of holes dug by rabbits, making it a bumpy ride with the wheelchair. We settled briefly at a shady spot under some trees where some bunnies had gathered, and lured them with pellets. I was worried that they might bite our fingers, but they were docile and friendly, nibbling only on the food that was offered. “Kawaii!” Lilia said. “Cute!”

Although the rabbits are, for all intents and purposes, wild, they are supposedly descendants of pet rabbits kept at a long-ago school. The story goes that in 1971 schoolchildren released eight of these creatures on the island, and then they began to proliferate, as rabbits do, Now the island is designated as a national park and is home to around 700 bunnies.

We wandered slowly back toward the port, dispensing pellets as we went. The rabbits are now protected from hunters, dogs, and cats (which are prohibited on the island). Signs warn visitors not to feed them on the road, in order to keep them safely out of the way of oncoming cars. From their appearance, they seem mostly healthy and well cared for. The island itself is now a family-friendly place with a campground and a spa, where people from all over the world gather peacefully.

As we lined up for the ferry to return home, my only regret was that we couldn’t stay longer. Then again, now that we knew how to get there, we could always go back.

Suzanne Kamata is the author of the YA novels Gadget Girl: The Art of Being Invisible and Screaming Divas, both of which feature diversity as a theme. She was the editor of Love You to Pieces: Creative Writers on Raising a Child with Special Needs . Her nonfiction book A Girls’ Guide to the Islands, about traveling in Japan with her daughter who has multiple disabilities, was published in 2017. This is an edited version of an essay that appeared in Eye-Ai Magazine.

The sequel to Gadget Girl will be published in late 2018/early 2019.

0 Comments